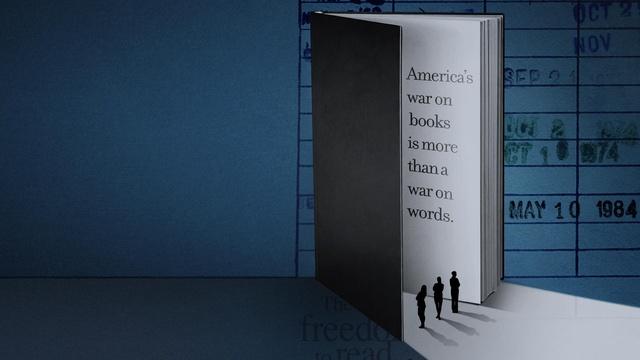

What is Critical Race Theory?

From: Manchester Ink Link and GSNC

By Ryan Lessard

For the past five or six years, Nashua Police Lt. Carlos Camacho has been teaching new officers about implicit bias, whether it’s an unconscious bias toward people of other races, genders, socioeconomic class or sexual orientation. As part of the training, he shows the officers how they tend to gravitate toward others they find commonality with, reveals the ways they perceive people who are different and encourages them to learn about those differences and find common ground with them.

Implicit bias, he said, is something everybody has.

“You have to be aware of it in order to do a better job,” Camacho said.

Strengthening that curriculum and expanding it from two hours to 16 hours in the state police academy was one of the many bipartisan reforms that came out of last year’s Commission on Law Enforcement Accountability, Community and Transparency (LEACT) in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin.

But legislative language included in a $13 million state budget would make that training impossible, according to Manchester NAACP President James McKim.

The language was pulled from HB 544, which was tabled by the House Executive Departments and Administration Committee. Among other things, it would ban the dissemination of “divisive concepts” such as the existence of an unconscious bias or a privilege that a race may have, by any state training programs, state contractors or grant recipients.

McKim and other former LEACT members such as American Civil Liberties New Hampshire Legal Director Gilles Bissonnette, objected to the bill in the House because they said it presented an unconstitutional restriction on free speech and would “set back progress” on addressing systemic barriers and discrimination faced by people of color and other marginalized groups.

“If this were to pass, we couldn’t even talk about this bill. How crazy is that?” McKim said.

While it is never mentioned directly in the bill, proponents and opponents say it is designed to prohibit the use of a controversial body of academic study known as Critical Race Theory (CRT). But both sides can’t seem to agree on what Critical Race Theory even is.

Opponents say it owes its roots to Marxist class conflict ideologies, adapted to model a race conflict dynamic instead, and they say it is inherently racist — essentially casting all white people as racist oppressors.

Adam Waldeck is the president of 1776 Action, a newly formed group aimed at supporting efforts like HB 544 and stamping out the use of Critical Race Theory and similar schools of thought. He said they “abhor racism” and that it shouldn’t be minimized, but argue CRT is not the anti-racist curriculum it claims to be.

“We would argue that they are promoting racism. They are teaching people to be racist,” Waldeck said.

But Jonathan Wesley, an online professor and Senior Director of Equity and Inclusion in Academic Affairs for Southern New Hampshire University, said the opponents got it wrong.

“CRT was not modeled after Marxism. It was created because there was a gap in legal cases. While there can be some overlap as it relates to racism and classism, CRT is not a Marxist school of thought,” Wesley said.

As for whether CRT is racist, Wesley said that’s a misunderstanding of what the study attempts to do, which is to point out “what white people choose to ignore” by describing how systems discriminate against certain people and keep others in power based on race.

“CRT theory does not teach hate, it does not incite that one should feel guilty for being white,” Wesley said. “It's calling white people and others into a state of accountability that we cannot ignore race.”

“Everything is obsessed with race, and it’s teaching students to look around the classroom and make judgements based upon the color of their skin,” Waldeck said.

For Waldeck, these trainings are indoctrinating people into believing a false and hateful narrative about American history and that it creates, rather than reveals, racial division.

But that scene Waldeck describes, of students being asked to consider the skin color of others, is indeed a common part of cultural diversity training, according to Camacho, who now also serves as chairman of the Ethnic and Racial Disparity Committee under the Juvenile Justice Statewide Advisory Group. Though, its purpose is not to sow hate, but to acknowledge that each person has a different background and experience. And that’s just the starting point, he said.

At first, his cultural diversity training was for new Nashua recruits. Now, he co-teaches an expanded 16-hour course for every cadet who goes through the New Hampshire Police Standards and Training Academy.

Camacho covers cultural diversity and implicit bias training on the first day, and Assistant Safety Commissioner Eddie Edwards teaches procedural justice on the second day.

Camacho said one of the first steps is a “self-analysis,” where each individual considers the descriptors they already use for themselves or the groups they identify with. This can include things like white, Black, straight, gay, Catholic, atheist and so on. Then they’re asked to look around the room for others in their “like group.”

From there, Camacho shows them how they can “try to make your circle bigger” by including more and more people who are different from them.

Camacho compares this to a common experience in military boot camp, where a lonely cadet befriends someone from their hometown or someone who shares an interest or looks like them. But over the course of the boot camp, every cadet starts to see others in their troop as part of the one group.

During the course, they discuss recent cases in the news where a police response against Black citizens might be considered heavy handed and consider other ways they could have handled it. While some differing opinions are shared freely in discussion, Camacho said he almost never gets any negative feedback from the cadets, and he has never had an issue talking about the concept of white privilege, a concept Waldeck and others take issue with.

“They say it was very eye opening,” Camacho said.

Still, Waldeck argues CRT is uncompromising in perpetuating its own discrimination. Though, he has no problem with examining one’s own biases.

“That’s not a bad thing, in general. But this is advocacy. It’s totalitarian. They’re not teaching people how to think. They’re teaching them what to think,” Waldeck said.

Wesley said examining race is the first step to addressing inequities, which exist because of implicit bias against people of color on aggregate, over time.

“We cannot ignore race or we cannot be colorblind,” Wesley said.

Pointing out that the system has historically favored white people is not the same as arguing there is something inherently bad about whiteness, Wesley said.

“None of the literature says … that all white people are evil,” Wesley said.

The study of CRT holds that the general existence of racism is permanent throughout history, but that it is a learned behavior in individuals, ze said. Only by shining a light on that learned behavior, Wesley said, can one begin to correct it.

Camacho agrees.

“Everybody needs to be a part of the dialogue,” Camacho said. “We need to learn our history.”

McKim said one of the reasons Critical Race Theory has become the subject of political debate is an inherent divergence in perception.

An August NPR/Ipsos poll found that only 50 percent of white Americans agree systemic racism exists, compared to 83 percent of Black people.

Similarly, when asked if white people have an advantage in our society, compared to people of color, almost the same breakdown in perception exists (49 percent white Americans vs 83 percent Black Americans).

But McKim said the reality of racist inequality can be shown in hard data, particularly in the realm of public health. The COVID-19 pandemic has cast existing disparities in sharp relief, he said.

While Black people make up only 1.4 percent of the New Hampshire population, they represent 5.3 percent of the COVID-19 cases. And though white residents make up 91 percent of the overall population, they make up only 73 percent of the cases. This pattern repeats elsewhere in the country.

“There’s a disparity there. The systemic disparity is people of color don’t have access because of the way the systems operate, and once they’re in the systems, the procedures are discriminatory. And implicit bias creeps in as well,” McKim said. “It’s not always intentional.”

He said the language of HB 544 seems to be an effort to keep the state white and male dominated, by prohibiting any discussion of what that means and by denying the existence of any current discrimination.

But McKim said even if it passes, it will likely face legal challenges.

“It was pretty much a word-for-word lift from the Trump administration executive order, which was found to be unconstitutional by a district court in Northern California,” McKim said, referring to President Trump’s order last fall banning certain diversity trainings in federal agencies, contractors or grant recipients, calling it “anti-American.”

President Biden overturned that order as one of his first official acts in January. Since then, the battlefield has moved to the state level.

1776 Action is a 501c4 nonprofit which owes its name to the 1776 Commission established by Trump as a response to some efforts to tell the history of racial oppression in America, which the former president derided as toxic.

Waldeck said they did not actively lobby New Hampshire lawmakers to pass the bill, but they paid for radio air time to run an advertisement in April before the House committee voted to table the bill.

“Last year, radicals destroyed statues and burned cities,” the narrator in the ad states. “Now, in many New Hampshire schools, they’re brainwashing our children to hate America and each other.”

Waldeck said they also texted 100,000 New Hampshire voters with the video form of the ad and got it played on Fox News when the network covered the story.

Their website, 1776action.org/newhampshire, invites residents to sign a pledge to “restore truthful, patriotic education” in the classroom.

If the budget passes with this language in it, McKim said it would likely be used by Republican lawmakers who championed the language to celebrate the victory in their next election. If it doesn’t get signed into law, Waldeck said they’ll hold ‘no’ votes accountable.

“We want this to be something that people vote on when they go to the polls,” Waldeck said.

After New Hampshire, 1776 Action will turn its attention to the school board in Loudoun County, Virginia, which is clashing with parents over CRT-based diversity training in the classroom.

So far, the language has attracted opposition from all corners of the Granite State. The Business and Industry Administration, along with 225 independent businesses and nonprofits, said it “sends the wrong message to employers who recognize the importance of open, honest and yes, sometimes difficult and uncomfortable conversations with their employees about the issue of race and gender discrimination.”

BIA President Jim Roche said it would be bad for business, it would leave employers open to discrimination litigation and would be a “black eye” on the state.

A dozen leading environmental and conservation groups also came out against the legislation.

“We need to engage in active listening, deep and sometimes uncomfortable conversation, and authentic action to learn about and reverse the effects that both recent history, and centuries of systemic racism, have had on equitable and inclusive access to the outdoors,” the environmental groups said in a joint letter to Gov. Chris Sununu and state Senate leaders.

Before the bill was tabled in the House, Sununu said he would probably veto the bill because it too broadly limits free speech. But it’s unclear if it will be a deal breaker in the budget.

The full House approved the state budget with the language included. It is now being reviewed by the Senate.

This article is part of a multiyear project exploring race and equity in New Hampshire produced by the partners of The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

Return to the

Real Talk

Main Page

Watch Online

TV Schedule

-

ratified

Independent Lens

Saturday, 3/7 at 12:00 P.M. on WORLD -

ola hou - journey to new york fashion week

Pacific Heartbeat

Saturday, 3/14 at 7:00 P.M. on WORLD -

sister una lived a good death

Independent Lens

Tuesday, 3/17 at 2:30 P.M. on EXPLORE -

daughters of the waves

Pacific Heartbeat

Monday, 3/23 at 7:00 P.M. on WORLD